The Science of Overtraining

Signs, Symptoms, and Recovery Tips

Are You Training Too Hard? Recognizing the Signs of Overtraining

You’re dedicated. You grind through early mornings, push through fatigue, and pride yourself on never skipping a session. But what happens when that discipline starts working against you? When motivation turns to burnout, and progress turns into plateaus or even setbacks?

In the world of fitness, “more” isn’t always better.

Overtraining is the silent saboteur of performance—a condition that affects everyone from elite athletes to weekend warriors. It creeps in gradually, often disguised as normal fatigue or just a “bad week,” until you find yourself dealing with nagging injuries, emotional exhaustion, and a frustrating dip in performance.

If you’ve been pushing your limits and something feels off—your sleep is suffering, motivation is gone, or your gains have stalled—it might be more than just a rough patch. You could be experiencing overtraining symptoms, a physiological and psychological state where your body can no longer keep up with the stress you’re placing on it.

This guide explores the science of overtraining—from the underlying causes and hormonal shifts to the warning signs, diagnostic tools, and best recovery methods. Whether you're a seasoned lifter, a high-performing athlete, or a dedicated gym-goer, this in-depth article will help you train smarter, avoid burnout, and reclaim control of your fitness journey.

Let’s dig into what overtraining really is—and what to do when your body says “enough.”

What Is Overtraining?

Imagine this: You’re doing everything right—working out consistently, adding more reps, squeezing in extra cardio, maybe even skipping rest days because you’re chasing that next level of performance. But instead of getting stronger, you’re feeling weaker. Instead of energizing you, your workouts leave you drained. You’re not lazy. You’re not broken. You might just be overtrained.

Overtraining is a physiological and psychological state that occurs when your body is exposed to more stress than it can recover from. It’s not just “training hard”—it’s training hard without enough recovery. Your muscles, nervous system, and hormones simply can't keep up with the relentless demand for performance, and things begin to unravel.

It starts subtly—slightly lower energy, a missed PR, poor sleep—but over time, the signs grow louder: chronic fatigue, mood swings, frequent injuries, and plateaued (or declining) performance.

Here’s the nuance:

Overtraining isn’t always a full-blown crash. It exists on a spectrum:

🟡 Functional Overreaching (FOR): A short-term dip in performance that leads to long-term gains—if followed by recovery. This is actually a smart strategy used in advanced training cycles.

🔴 Non-Functional Overreaching (NFOR): A more serious state where performance drops for weeks and recovery isn't fast. Gains stall or regress.

⚠️ Overtraining Syndrome (OTS): The most severe end of the spectrum, where performance, mood, metabolism, and even immune health are significantly compromised. Recovery can take months, and medical intervention is often necessary.

The key takeaway? Overtraining isn’t about doing too much once—it’s about consistently doing too much without listening to your body. And it’s more common than you think.

What Causes Overtraining?

At its core, overtraining is the result of doing more than your body can handle—and failing to give it enough time or resources to recover. But it’s rarely caused by just one factor. Instead, it’s often the accumulation of multiple stressors—some obvious, some hidden—that tip the balance from productive training to performance decline.

Let’s break down the most common causes of overtraining and how they interact:

High Training Volume or Intensity

You’ve heard it before: “Go hard or go home.” But constantly training at high intensities—without adequate rest between sessions—can overwhelm your body’s recovery systems.

High-volume programs (e.g., daily two-hour gym sessions, frequent double training days)

Frequent max-effort lifts or sprint work with minimal rest days

High-rep hypertrophy work layered on top of endurance training

While these strategies can be effective when programmed correctly, doing them chronically without variation leads to central nervous system (CNS) fatigue, muscular breakdown, and systemic stress. Without strategic deloads or programmed rest, even the most resilient athletes will eventually hit a wall.

Poor Sleep and Recovery Hygiene

Sleep is the cornerstone of physical and mental recovery. It’s during deep sleep that your body:

Releases growth hormone

Repairs muscle fibers

Replenishes glycogen

Regulates cortisol and other key hormones

When you consistently get less than 7–8 hours of quality sleep, your nervous system stays overstimulated. Add that to a high training load and your risk of overtraining symptoms multiplies. Even short-term sleep deprivation (like 3–4 nights in a row) has been shown to impair reaction time, reduce motivation, and elevate inflammation—all red flags for overreaching.

Inadequate Nutrition and Low Energy Availability

Your body needs fuel to perform—and even more to recover. If you’re not eating enough to match your training demands, your body starts cutting corners:

Muscle protein synthesis slows down

Hormonal balance (testosterone, estrogen, thyroid) becomes disrupted

Immune function weakens

Fatigue increases even at lower workloads

Low energy availability is especially common in athletes who are trying to lose fat or maintain a “lean” physique year-round. Combine that with intense training, and you have a recipe for overtraining and metabolic slowdown.

Key culprits:

Skipping meals post-workout

Chronically low-carb diets during high training loads

Under-eating due to appetite suppression or external pressure

Psychological and Emotional Stress

It’s easy to forget that stress is cumulative. Your body doesn’t differentiate between a tough workout, a brutal work deadline, a breakup, or poor sleep. They all activate the sympathetic nervous system, increasing cortisol and placing a load on your body’s recovery capacity.

If you're dealing with high emotional stress, anxiety, or mental burnout—and still pushing yourself in the gym—your nervous system may be running on fumes.

Warning signs include:

Irritability or mood swings

Poor sleep despite exhaustion

Emotional flatness or depression

Feeling “wired but tired”

Training through this state can drive you deeper into overtraining, even if your actual workout volume is reasonable.

Lack of Program Periodization

One of the biggest hidden causes of overtraining is simply poor programming. Without built-in cycles of intensity, rest, and progression, your body never gets a chance to fully recover and adapt.

Periodization solves this by organizing training into phases:

Volume vs. intensity weeks

Strategic deloads

Restorative cycles (lower-load, mobility-focused blocks)

Seasonal focus shifts (e.g., hypertrophy → strength → power)

Athletes who train at the same intensity year-round—without variation—are the most at risk. Without intelligent design, even well-structured training can become counterproductive over time.

Bonus Culprit: Social Media & "Hustle Culture"

Let’s not ignore the influence of online fitness culture. Seeing others train 24/7 can make rest feel like weakness. Many athletes ignore the early signs of burnout because they fear falling behind or losing progress. But here’s the truth: growth happens in recovery. Overtraining is not a badge of honor—it’s a performance killer.

Common Overtraining Symptoms to Watch For

Spotting overtraining symptoms early is critical. Here's what to look for—both physically and mentally.

Physical Symptoms

Persistent fatigue that doesn’t go away with rest

Decreased performance despite increased effort

Elevated resting heart rate

Increased soreness or injuries

Frequent illness due to a suppressed immune system

Menstrual irregularities in women

Weight loss or difficulty maintaining muscle mass

Mental and Emotional Symptoms

Irritability or mood swings

Loss of motivation

Sleep disturbances

Depression or anxiety

Reduced concentration and focus

Important: Many athletes write these off as “just tired” or “in a slump,” which leads to longer recovery and potential injury.

How to Diagnose Overtraining (and When to Seek Help)

One of the most frustrating things about overtraining symptoms is that they don’t come with flashing warning lights or a simple test result. Diagnosing overtraining can feel like solving a puzzle—because it’s often what’s not there (like progress, energy, or motivation) that gives it away.

Medically speaking, overtraining is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. That means doctors and sports professionals rule out other conditions—like anemia, thyroid issues, or infections—before labeling your condition as Overtraining Syndrome (OTS). But if you know what to look for, there are early warning signs and tools that can help you spot the problem before it derails your fitness.

Here are five smart ways to detect overtraining before it goes too far:

Resting Heart Rate (RHR) Tracking

Your heart doesn’t lie. If your resting heart rate is consistently elevated—we’re talking 5–10 beats per minute above your normal baseline for several mornings in a row—it could be a sign your autonomic nervous system is in overdrive.

Try this:

Check your heart rate first thing each morning before getting out of bed.

Log it daily in an app or notebook.

If it’s trending up without explanation, that’s your red flag.

Athletes often mistake this spike for a cardio improvement plateau—but it’s actually your body saying, “Slow down.”

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Monitoring

HRV measures the variation between heartbeats. Higher variability typically means better recovery and nervous system balance. Lower HRV—especially when sustained for several days—can indicate that your body is stuck in “fight or flight” mode.

Wearables like WHOOP, Oura Ring, and Garmin track HRV automatically. What you want to watch for:

A sharp drop in HRV from your baseline

HRV that remains suppressed despite sleep and rest

HRV drops paired with fatigue, mood changes, or performance dips

This is one of the best objective tools we have to assess cumulative stress—both physical and emotional.

Blood Test Markers

When in doubt, go deeper. Blood tests can provide a more definitive look at how your body is handling stress and recovery.

Here are some markers that matter:

Cortisol: Often elevated in overtrained individuals

Testosterone: May drop in both men and women due to chronic stress

TSH, T3, T4: Thyroid hormones that reflect metabolic function

CRP (C-Reactive Protein): A marker of systemic inflammation

Iron, B12, D3: Deficiencies that can mimic overtraining symptoms

If you’re experiencing prolonged fatigue or mood issues, it’s worth getting a panel done through a sports doctor or functional medicine practitioner.

Mood and Motivation Shifts (Psychological Tools)

Overtraining isn’t just physical—it hits your mind, too. Emotional symptoms are often the first to show up:

You’re dragging yourself to the gym

You feel emotionally flat, anxious, or snappy

You’ve lost your drive to train altogether

Tools like the POMS (Profile of Mood States) questionnaire can help you quantify your emotional shifts. Even just journaling how you feel after workouts can highlight patterns of burnout.

Tip: If training no longer gives you joy, energy, or a sense of accomplishment—it might be time to step back.

Sudden Performance Drop-Off

Perhaps the most obvious—but also most ignored—sign of overtraining is a clear decline in performance despite consistent effort. If your:

Lifts are getting weaker

Endurance is tanking

Reaction times are slower

Workouts feel harder than they should

...then something’s off. Especially if these changes happen over several weeks and you haven’t changed your diet or routine, it’s not just a bad training cycle—it could be systemic fatigue.

When to Seek Professional Help

If your symptoms:

Last longer than 2–3 weeks

Don’t respond to rest or deloading

Interfere with sleep, mood, or everyday life

...it’s time to see a qualified professional. A sports medicine doctor, exercise physiologist, or functional health practitioner can run deeper diagnostics and help rule out other conditions while guiding your recovery plan.

Remember: getting help early can mean the difference between a 2-week reset and a 3-month setback.

Recovery Strategies: How to Bounce Back from Overtraining

If your body is waving the white flag, don’t ignore it. Overtraining isn't a sign of weakness—it's your body asking for a reset. The good news? With the right recovery strategy, you can come back stronger, smarter, and more resilient than ever.

Here’s how to rebuild, replenish, and reclaim your performance.

Total Rest or a Smart Deload

First rule of recovery: Stop digging.

If you’re experiencing full-blown overtraining symptoms, the only prescription that works is rest. That means pressing pause on high-intensity training for 7 to 14 days—no heavy lifting, no sprints, no pushing through the pain.

But if you’ve caught the signs early, a deload week may be enough. This involves:

Reducing volume and intensity by 40–60%

Swapping out heavy lifts for technique work or mobility

Focusing on movement quality over quantity

Think of it as a system reboot—not a step backward, but a launchpad forward.

Sleep: Your Ultimate Recovery Weapon

Sleep isn’t just rest—it’s repair. During deep sleep stages, your body:

Releases growth hormone

Rebuilds muscle tissue

Balances cortisol and testosterone

Consolidates motor learning from training

To maximize recovery, aim for 8–9 hours of quality sleep each night. Some tips to upgrade your sleep:

Use blackout curtains and keep your room cool (~65°F / 18°C)

Cut screen time 60 minutes before bed

Try magnesium glycinate or a hot bath to wind down

Nap smartly (15–20 minutes max) to recharge your CNS

No supplement or superfood can replace consistent, deep sleep.

Nutrition Reset: Eat to Heal

Training breaks down tissue. Food builds it back up. Period.

When recovering from overtraining, under-fueling is the #1 mistake to avoid. Here’s what your body needs:

Increased calorie intake, especially from complex carbohydrates and high-quality protein

Hydration, with electrolytes if needed to restore fluid balance

Anti-inflammatory foods like salmon, leafy greens, turmeric, berries, ginger, and omega-3s

You may feel less hungry when overtrained—but this is when eating well matters most. Your muscles, hormones, and immune system all depend on it.

Stress Management: Reset the Nervous System

Overtraining doesn’t just drain your body—it burns out your mind. The fix? Activate your parasympathetic nervous system (a.k.a. your recovery mode).

Daily recovery habits to reduce systemic stress:

Box breathing (4-4-4-4) or extended exhales

Meditation or guided mindfulness—try Calm, Headspace, or Insight Timer

Journaling—release mental tension before it manifests physically

Nature therapy—time in green spaces is scientifically linked to lower cortisol

Tip: Combine breathwork and movement (like slow yoga or walking meditations) for a double hit of recovery.

Active Recovery: Move Without Stress

Once the worst symptoms subside, low-intensity movement helps restore circulation, joint mobility, and mood—without taxing the system.

Excellent active recovery choices include:

Brisk walking, ideally outdoors for added mental benefits

Swimming or water aerobics for low-impact circulation

Mobility circuits or foam rolling to improve range of motion

Yin yoga or light stretching to calm the nervous system

Think of active recovery as motion medicine—it gets blood flowing, releases tension, and accelerates healing without setting you back.

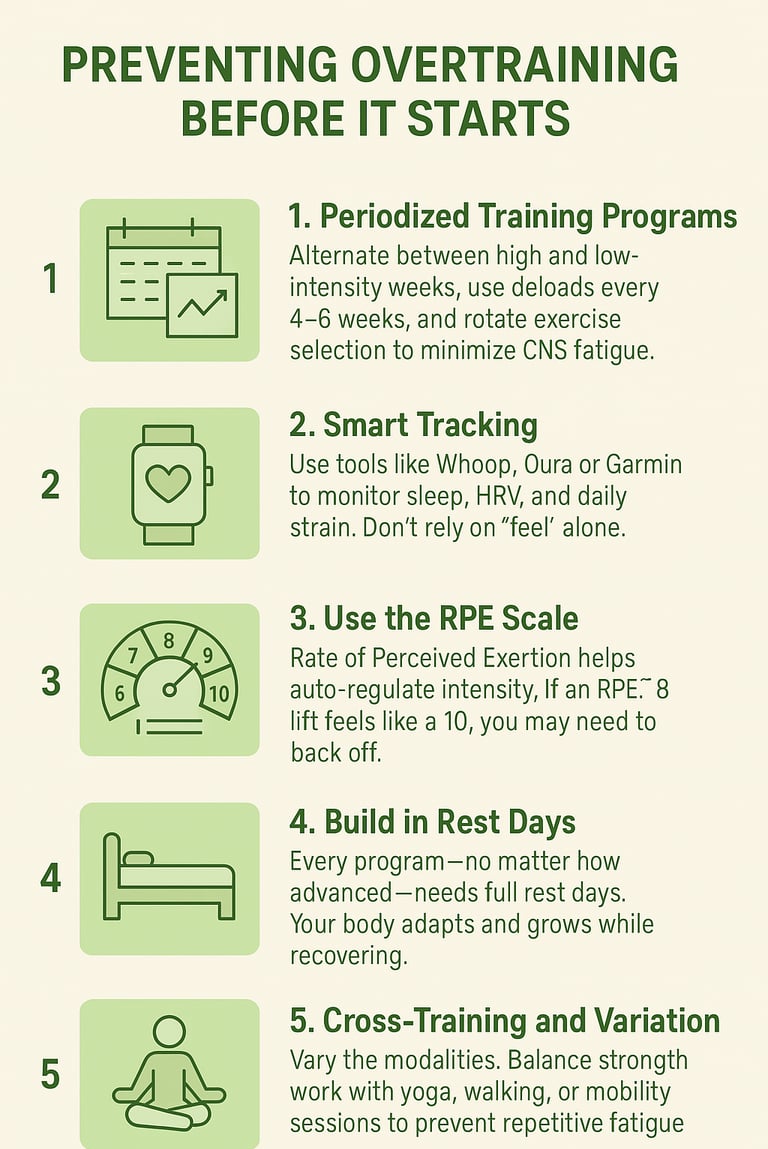

Preventing Overtraining Before It Starts

The best way to deal with overtraining? Never get there in the first place. Prevention isn’t just about taking rest days—it’s about training with intention, not ego.

By building smarter structure into your routine, you can stay in that sweet spot of consistent progress without burning out. Here’s how to stay strong, sharp, and sustainable.

Periodized Training: Train Smarter, Not Harder

Think of your training like a wave, not a straight line. Periodization helps you ride that wave by alternating intensity, volume, and focus throughout the year.

Include deloads every 4–6 weeks

Cycle through different goals (e.g. strength → hypertrophy → mobility)

Rotate exercises to reduce central nervous system (CNS) fatigue

Tip: Explore our in-depth guide to training periodization for smarter, more effective workouts.

Smart Tracking: Data > Guesswork

You wouldn’t drive a race car without a dashboard—so why train without feedback?

Wearables like Whoop, Oura, Apple Watch, or Garmin give you real-time insights into:

Sleep quality

Heart rate variability (HRV)

Daily strain and recovery balance

Don’t rely on motivation or muscle soreness to gauge readiness. Let your body’s data guide when to push and when to pause.

Master the RPE Scale

The Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) is a simple but powerful tool to self-regulate your training intensity.

If a set is supposed to be an RPE 8 (2 reps left in the tank) but feels like a 10—that’s a sign to back off. Your nervous system might be under-recovered, even if the weights haven’t changed.

Use RPE to:

Auto-adjust for daily readiness

Prevent "ego lifting" on off days

Stay consistent without overreaching

Rest Days Are Training Days

Here’s the mindset shift: Rest is part of your training plan. It’s not a break from progress—it’s where the progress happens.

Take 1–2 full rest days per week

On hard training weeks, consider an extra day off or a low-impact session

Use rest days to mentally reset, eat well, and prioritize sleep

Recovery isn’t the opposite of training—it completes the cycle.

Cross-Training and Movement Variety

Repetition builds skill—but too much of the same movement pattern leads to overuse injuries and burnout. Cross-training helps you stay active while giving fatigued systems a break.

Mix it up with:

Yoga or Pilates for mobility and core activation

Hiking or swimming for low-impact endurance

Light cycling or rowing for aerobic base building

This keeps training fun, fresh, and neurologically stimulating—while reducing physical wear and tear.

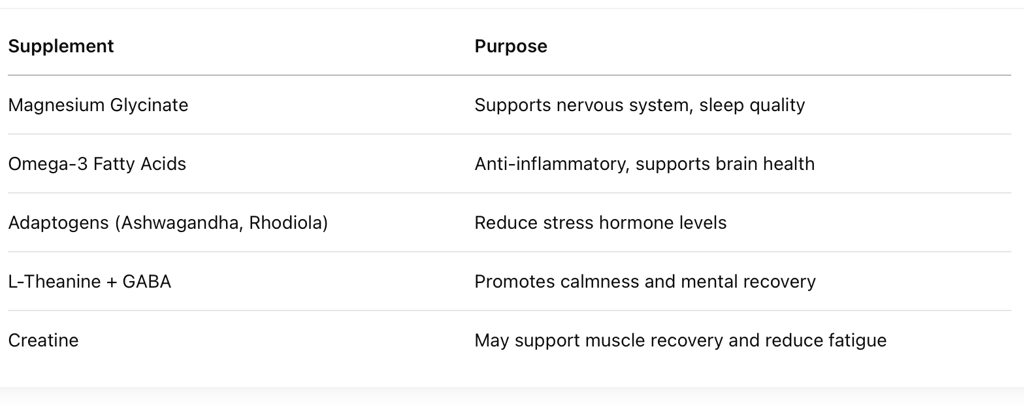

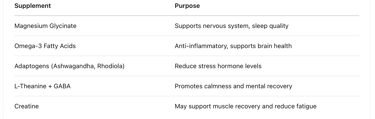

The Role of Supplements in Recovery

Let’s be clear: no supplement can fix overtraining. If you’re sleep-deprived, under-eating, and training too hard, popping pills or powders won’t save your performance. Rest, nutrition, and stress management are your foundation.

However, when those pillars are in place, strategic supplementation can support and accelerate recovery—especially when your body is under strain or playing catch-up from a deficit.

Here are a few research-backed options that may help:

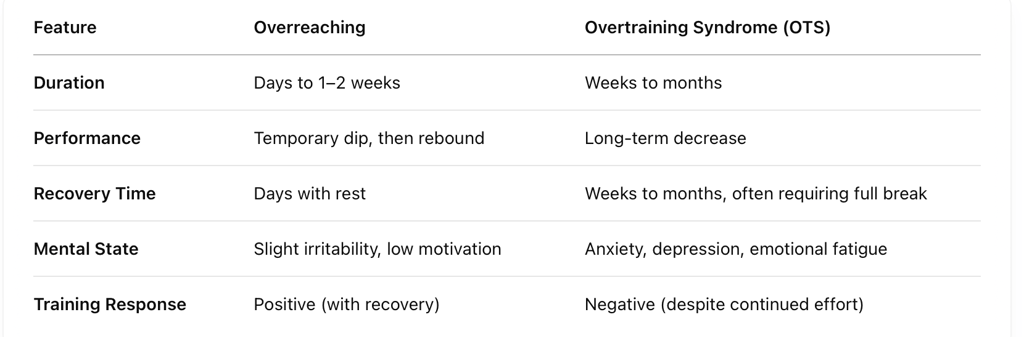

Overtraining vs. Overreaching: Know the Difference

Not all fatigue is bad. In fact, a certain level of stress is necessary for your body to grow stronger. But when does productive fatigue cross the line into something more harmful?

Understanding the difference between overreaching and overtraining is critical for any athlete or fitness enthusiast who wants to train hard—without burning out.

Overreaching is a short-term, intentional spike in training stress. You might feel a temporary dip in performance, but with adequate rest, it leads to super compensation—meaning you come back even stronger.

Overtraining, on the other hand, is a chronic state where performance, mood, and physical health deteriorate. It often takes weeks or even months to fully recover and can derail long-term progress.

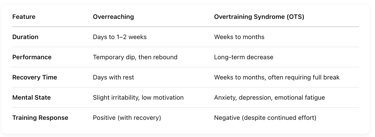

The key distinction lies in recovery time and adaptation:

Overreaching is like pushing the accelerator to go faster… Overtraining is like riding the brakes with the gas pedal still down.

Here’s a quick comparison to clarify:

Knowing which side of the line you're on can help you take the right action: either lean into recovery now and come back stronger—or risk hitting the wall later.

Who Is Most at Risk of Overtraining?

Overtraining doesn’t just affect elite athletes grinding through double sessions. In reality, it can sneak up on anyone—especially when training stress stacks up alongside life stress.

Here are the groups most vulnerable to overtraining symptoms:

Elite and amateur athletes: High expectations, packed training schedules, and pressure to perform can lead to chronic overload—especially during competition prep or multi-sport training.

High-volume lifters and endurance athletes: Training for marathons, triathlons, or hypertrophy gains often involves long sessions, limited rest days, and high intensity—leaving little room for recovery.

People on calorie-restricted or low-carb diets: Without enough fuel, the body can’t recover from stress. Athletes trying to lose weight while training hard are at particular risk of hormonal disruptions and fatigue.

Individuals with high job/life stress: Long work hours, poor sleep, parenting demands, and emotional strain all tax the nervous system. Layer intense workouts on top, and the system eventually cracks.

Type-A personalities or perfectionists: The “no days off” mindset may be admirable—but it’s also dangerous. People who push through exhaustion, ignore pain, or treat rest as failure often ignore early warning signs.

Even casual gym-goers aren’t immune. If you’re doing fasted HIIT, eating in a deficit, working long hours, and skipping rest days, you could still develop overtraining symptoms. It’s not about being a professional—it’s about total stress load versus recovery capacity.

⚠️ Overtraining isn’t just about exercise—it’s about the full picture of physical, mental, and emotional load.

Final Thoughts: Train Hard, Recover Harder

Understanding overtraining symptoms can be the difference between steady progress and hitting a wall. Training intensity is important—but recovery is where the magic happens. By listening to your body, tracking the signs, and incorporating rest and nutrition into your regimen, you’ll train longer, stay healthier, and perform better.

References

Meeusen, R., Duclos, M., Foster, C., Fry, A., Gleeson, M., Nieman, D., ... & Urhausen, A. (2013). Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the Overtraining Syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(1), 1-24.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.730061Kreher, J. B., & Schwartz, J. B. (2012). Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health, 4(2), 128–138.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738111434406Fry, A. C., & Kraemer, W. J. (1997). Resistance exercise overtraining and overreaching: neuroendocrine responses. Sports Medicine, 23(2), 106–129.

https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199723020-00004Halson, S. L. (2014). Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Medicine, 44(Suppl 2), 139–147.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0253-zBudgett, R. (1998). Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndrome. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(2), 107–110.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.32.2.107Schaal, K., Tafflet, M., Nassif, H., Thibault, V., Pichard, C., Alcotte, M., ... & Toussaint, J. F. (2011). Psychological balance in high-level athletes: Gender-based differences and sport-specific patterns. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e19007.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019007Grandou, C., Wallace, L., Impellizzeri, F. M., Allen, N. G., & Coutts, A. J. (2020). Overtraining in resistance exercise: An exploratory systematic review and methodological appraisal of the literature. Sports Medicine, 50, 815–828.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01242-9Soligard, T., Schwellnus, M., Alonso, J. M., Bahr, R., Clarsen, B., Dijkstra, H. P., ... & Engebretsen, L. (2016). How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1030–1041.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096581Peake, J. M., Neubauer, O., Walsh, N. P., & Simpson, R. J. (2017). Recovery of the immune system after exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 122(5), 1077–1087.

https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00622.2016