Good Carbs vs Bad Carbs

The Glycemic Index Myth Exposed

Rethinking ‘Good’ vs ‘Bad’ Carbs

Are whole wheat toast and candy bars really worlds apart for your body? For years, Americans have been told that complex carbohydrates like whole grains are “good carbs” – a cornerstone of a healthy diet – while simple sugars are “bad carbs” to be avoided. Food companies splash labels like “wholesome whole grains” on cereal boxes, and dietitians extol fruit-sweetened granola bars over candy. Meanwhile, sugar gets cast as the arch-villain. But what if we told you that the glycemic index of your morning toast isn’t much better than that of table sugar? In fact, on the standard glycemic index (GI) scale (where pure glucose = 100), white bread clocks in around 75, higher than refined sugar’s GI of about 65. Even whole wheat bread isn’t far behind at ~74 pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Shocking, right?

In this in-depth exploration, we’ll uncover how the simplistic “good vs bad carb” narrative falls apart under scientific scrutiny. You’ll learn how the glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) of common foods reveal surprising truths – like how a granola bar marketed as healthy can send your blood sugar soaring similar to a candy bar. We’ll also expose how the food industry, often with backing from dietitians and nutrition coaches on their payroll, has misled the public about carbohydrates. Most importantly, we’ll show why portion size – how much you eat – is the ultimate factor in blood sugar impact, trumping whether a carb is “whole grain” or “refined.” By the end, you’ll be equipped (and maybe a bit outraged) to make wiser carb choices based on science, not marketing. Let’s dive in.

What Are Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load?

Glycemic Index (GI) is a scientific scale that ranks how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food raises your blood glucose levels compared to pure glucose (which has a GI of 100).

High-GI foods (GI >70) are rapidly digested and absorbed, causing sharp spikes in blood sugar.

Low-GI foods (GI <55) digest more slowly, resulting in a gentler rise.

However, GI only tells part of the story — it doesn’t account for how much of the food you’re actually eating. That’s where Glycemic Load (GL) comes in.

Glycemic Load = GI × grams of carbs per serving ÷ 100

This means:

A food with a high GI but low carb content (like watermelon) may still have a low GL and minimal impact.

A food with a moderate GI but large portion (like a giant bowl of brown rice) may have a high GL, spiking blood sugar significantly.

In short:

GI = speed

GL = speed × quantity

If you want to learn more about how GI and GL work (including detailed charts and examples), check out our full explainer:

👉 Balanced Blood Sugar, Naturally: GI vs GL Explained

The Myth of “Good” vs “Bad” Carbohydrates

For decades, carbohydrates have been labeled as “complex” (slow-digesting, therefore “good”) or “simple” (fast-digesting, therefore “bad”). Whole grains, brown rice, and veggies are grouped as good carbs, while table sugar, candy, and white bread get shoved into the bad carb corner. This black-and-white classification is convenient for marketing – who wouldn’t want to buy products boasting “good carbs” only? – but it oversimplifies how carbs affect our bodies.

Glycemic Index doesn’t follow the good/bad script: The glycemic index is a scientific tool that ranks carbohydrate-containing foods by how quickly they raise blood glucose. Surprisingly, many so-called good carbs have high GI values, not much better than the bad carbs. For example, that whole-grain bread you choose over a cookie has a GI in the mid-70s, about the same as white bread pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov – which means it can raise blood sugar rapidly. Meanwhile, a chocolate candy bar might have a GI in the 40s because its fat content slows sugar absorption. In other words, your body can experience a blood sugar spike from “healthy” complex carbs that rivals or even exceeds the spike from an “unhealthy” sugary snack. Simply calling one food “good” and another “bad” doesn’t capture this nuance.

Complex vs simple – not so straightforward: The traditional idea was that complex carbohydrates (starches found in breads, grains, legumes) break down slowly, providing steady energy, whereas simple sugars cause quick spikes. However, research shows it’s not that straightforward. A plain baked potato (often thought of as a complex carb) has a GI of ~82 (using glucose as reference), higher than even white bread. And fructose (a simple sugar) has a GI of only 15. The rate of digestion depends on many factors – fiber content, protein and fat in the food, processing, and more – not just whether the carbohydrate’s structure is “complex” or “simple.” This is why an orange (filled with fiber) causes a gentler blood sugar rise than an equal amount of carbs from orange juice or candy. It’s also why a heavily processed “whole grain” cereal can act more like pure sugar in your bloodstream despite being labeled as a complex carb.

Whole wheat bread vs white bread – nearly identical GI: Many consumers assume whole wheat bread is dramatically better for blood sugar than white bread. Nutritionally, whole wheat does have more fiber and micronutrients. But in terms of glycemic response, whole wheat bread (GI ~74) is virtually the same as white bread (GI ~75) in its impact on blood glucosepmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. The fiber in two slices of whole wheat bread is simply not enough to offset the rush of starch turning to glucose once digested. So if you eat a large portion of whole wheat bread, your blood sugar may surge almost as quickly as if you downed the same amount of white bread or even straight table sugar.

The candy bar comparison: Consider this irony – a Snickers bar or similar chocolate-nut candy bar, often vilified as junk food, has a moderate GI because the peanuts and fat slow the absorption of sugar. That does not make candy bars a healthy choice (they’re loaded with sugar and calories), but it shows how glycemic index flips the script on good vs bad. In fact, one comprehensive table of GI values lists milk chocolate’s GI around 40 (low GI category), whereas a “healthy” granola bar made with rice crisps and dried fruit can register a high GI (≥70) in testing pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. To your body, 50 grams of carbs from that chewy granola bar may hit just as hard and fast as 50 grams of carbs from white bread or candy. The lesson: You can’t judge a carb by its cover – the impact on blood sugar can defy our expectations.

Glycemic Index vs. Glycemic Load: Why Portion Size Matters

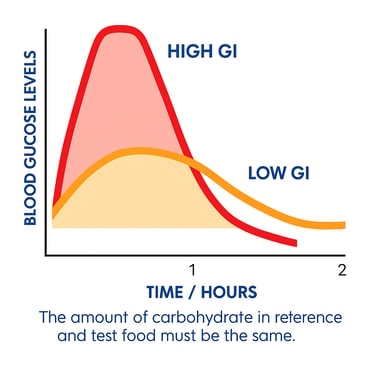

Figure: Illustration of blood glucose levels over 2 hours for a high-GI food (red curve) vs a low-GI food (orange curve), assuming equal carbohydrate amount. High-GI foods cause a sharp, rapid spike in blood glucose followed by a quick drop, whereas low-GI foods lead to a gentler rise and fall. However, in real life, the quantity of carbs consumed matters just as much as the quality – which is where glycemic load comes in.

Understanding glycemic index (GI) is only half the story. GI assigns a number to a food based on how quickly 50 grams of its carbohydrates raise blood sugar compared to pure glucose. But ask yourself: do you always eat exactly 50 grams of carbohydrate from that food in a serving? Probably not. This is where glycemic load (GL) becomes crucial. Glycemic load = GI * the amount of carbs in a serving / 100, and it reflects the total blood sugar rise caused by a typical portion of the food. In simpler terms, GL combines quality and quantity: it accounts for how fast the carbs turn to glucose (GI) and how many carbs you’re actually eating.

Why does this matter? Because a small serving of a high-GI food might not be a big deal, while a large serving of a moderate-GI food could wallop your bloodstream with glucose. “The glycemic index doesn’t account for how much of a food you eat,” notes Dr. Pankaj Shah, endocrinologist at Mayo Clinic. For example, watermelon has a very high GI (~76), similar to white bread. If we stopped there, you’d think watermelon is as “bad” as white bread. But a standard serving of watermelon has only ~11 grams of carbs (mostly water and fiber), whereas two slices of bread pack ~30 grams of carbs. So watermelon’s glycemic load is low – you’d have to eat a lot of it to get 50g of digestible carbs. In contrast, a big bowl of brown rice might have a moderate GI (~50), but if it contains 60-70g of carbohydrate, the glycemic load is high and can significantly elevate blood sugar. Portion size truly changes the equation.

Crucially, glycemic load captures the fact that “how much you eat” often determines the blood sugar impact more than the food’s GI ranking alone. You might get away with a small piece of cake (high GI, but low total carbs in a sliver) causing only a mild bump in glucose, whereas an enormous bowl of whole-grain pasta (lower GI per gram, but lots of grams!) could send you into a carb coma. This is why many dietitians emphasize carb counting for diabetics – because the total grams of carbohydrate consumed is a strong predictor of glycemic response pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. In fact, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has stated: “The total amount of carbohydrate consumed is a strong predictor of glycemic response, and thus monitoring total grams of carbohydrate ... remains a key strategy in achieving glycemic control.” pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. In plain English: how much carb you eat in a meal is usually more important than whether it’s from sugar or starch. This doesn’t mean GI is irrelevant – but it means dosing matters. A high-GI food eaten in tiny amounts may have a negligible effect, whereas even “good” carbs in large amounts can overload your system.

So, when you hear that “carrots have a high GI” or “fructose has a low GI,” remember to ask: How much would I realistically eat? Carrots do have a GI around 39 (fairly low actually), but even if it were higher, a serving of carrots has so little carbohydrate that it barely nudges blood sugar. On the other hand, glycemic load reveals why drinking a tall glass of orange juice (even 100% juice) can spike your blood sugar more than eating an entire orange – the juice delivers a large load of sugar quickly, whereas the whole orange provides less total sugar and that too is absorbed more slowly with fiber.

Portion Control: The Ultimate Blood Sugar Factor

We’ve hinted at it already, but it bears repeating with emphasis: portion size is king when it comes to blood sugar impact. This is the part the “good vs bad carb” narrative often neglects. You might have the healthiest whole-grain bread on the planet, but if you eat four slices in one sitting, your blood glucose will surge higher than it would from a single slice of white bread with a smear of jam. It’s a simple concept with huge implications.

Research consistently shows that larger servings elicit higher glycemic responses. In one controlled trial, scientists tested different portion sizes of oatmeal and found that as serving size increased, blood glucose iAUC (incremental area under the curve) and peak levels rose significantly pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. This held true even when they added extra sugar – portion size still predominated in determining the blood sugar curve. In practical terms, eating double the amount of the same food can result in roughly double the blood sugar impact pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Our bodies can handle a certain influx of glucose at a time; beyond that, the excess spills over into higher blood sugar peaks.

Think of your bloodstream like a highway: the glycemic index tells you how fast the “carbs cars” drive, but glycemic load (portion) tells you how many cars are on the road. A few speedsters on an empty highway (small portion of a high GI food) might not cause a traffic jam (glucose spike). But a huge convoy of trucks even going the speed limit (a massive portion of moderate-GI food) can clog things up quickly. Most modern diets’ problem isn’t that we occasionally eat high-GI foods – it’s that we eat way too many total carbs in one meal. Oversized bagels, heaping pasta bowls, “supersized” fries – the portions are often unrealistic relative to what our bodies can metabolize without a big insulin surge.

It’s telling that diabetes management guidelines focus heavily on carbohydrate counting. This is basically a strategy to moderate the “load” of carbs per meal. Even for weight management and general health, paying attention to portion sizes of carbs can help avoid the rollercoaster of spikes and crashes. It’s not that GI doesn’t matter at all – ideally, one should aim for low-GI, high-fiber carbs and reasonable portions – but if you had to prioritize one factor for blood sugar stability, portion wins almost every timepmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

How the Food Industry Spins the Carb Story

If the science on carbs is more nuanced, why do we still hear such simplistic advice about “good carbs” and “bad carbs”? One big reason: the food industry has a vested interest in shaping the carb narrative. From sugary cereal manufacturers to bread companies, many have spent decades funding research, marketing campaigns, and even educational programs to influence how we think about carbohydrates.

Consider this: Coca-Cola has paid “nutrition experts” and dietitians to mention soda as a healthy snack in media outlets. In a 2015 example reported by the Associated Press, Coke enlisted dietitians during American Heart Month to include a mini-can of Coca-Cola as a “refreshing beverage option” in their meal suggestions. The strategy was to push the idea that portion-controlled treats (like a small soda) can fit into a healthy lifestyle. While a mini 7.5-ounce Coke might indeed be a smaller sugar load than a 20-ounce bottle, the underlying intent was to keep soda in the “acceptable” category of consumers’ minds – perhaps as a “good carb” treat in moderation.

This kind of partnership is not an isolated case. Food companies regularly work behind the scenes with dietitians and health coaches to cast their products in a favorable light. According to the AP report, Coca-Cola’s spokesperson admitted, “We have a network of dietitians we work with... Every big brand works with bloggers or has paid talent.”Companies like Kellogg’s and General Mills have provided continuing education classes for dietitians and funded studies that conveniently highlight the “benefits” of their sugary cereals or refined grain products. The result is subtle: you might read an article by a credentialed nutritionist touting the “whole grain goodness” of a breakfast cereal that just happens to be made by General Mills, or recommending “sensible snacks” that include a certain brand’s granola bars. These experts might genuinely believe in what they’re saying – but it’s often because they’ve been exposed to industry-sponsored information that downplays sugar content or exaggerates the benefits of added fiber.

“Good carb” buzzwords are marketing gold: Terms like “whole grain,” “organic cane sugar,” “low glycemic” are slapped on products to signal they are “better” carbs. A granola bar made with “organic brown rice syrup” (a fancy name for sugar) and oats may be perceived as healthier than a candy bar with refined sugar. In reality, your body doesn’t care if sugar is brown or white – it metabolizes into glucose just the same. Whole grains in that cookie? Nice for fiber, but they won’t prevent a blood sugar spike if there’s still a lot of total carbs and added sweeteners. Food marketers routinely exploit these perceptions, promoting, for instance, that their cereal “has whole grains so it’s a good carb!” even though it may contain 10–15 grams of sugar per serving. Consumers trying to do the right thing end up eating a bowl of what is essentially sugar-frosted grain, under the impression it’s healthy.

Moreover, the portion size angle is often glossed over by industry messaging. The focus is on what you eat, not how much. It’s more profitable for a company if you believe switching from white bread to whole grain bread is the key – rather than simply eating less bread overall. That’s why you’ll see campaigns urging people to “make half your grains whole” (which is fine) but rarely will you see a food company ad telling you to eat fewer slices of bread. Even Coca-Cola’s tactic was to push smaller cans of soda as a solution, rather than addressing whether you need that soda at all. It’s portion spin: they acknowledge portion size matters but use it to sell you “portion-controlled” packs of cookies, 100-calorie snack packs, mini sodas – subtly encouraging you to keep consuming their products, just in smaller units.

Dietitians under influence: It’s important to note many dietitians and nutrition coaches are dedicated professionals who truly want the best for their clients. But their professional organizations and conferences often receive sponsorship from the likes of candy makers, soda companies, and processed food giants. For instance, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics – the largest body of dietitians – has in the past had corporate sponsors from the food and beverage industry, which has sparked controversies about unbiased advice. While not all dietitians succumb to industry influence, the temptation is there: a dietitian might be more likely to repeat that “all foods can fit” and “moderation is key” mantra (which is true to an extent) but avoid explicitly warning against overconsumption of sponsors’ products.

The bottom line is, the “good carb vs bad carb” story has been muddied by marketing interests. Consumers are left confused – you might think a muffin made with “real fruit” and whole grain is a good breakfast, not realizing it has the sugar equivalent of a candy bar. Or you switch from soda to fruit juice, thinking it’s healthier, but end up with a similar sugar load. To see through these tricks, it helps to rely on independent science (like GI/GL research) and keep an eye on portions, rather than packaging claims.

Comparing Common Carb Choices: Bread, Candy, and More

Let’s pit some everyday carb-rich foods head-to-head to see how they stack up in terms of glycemic impact. You might be surprised by how small the differences are between the “angels” and “devils” of the carb world:

White Bread vs. Table Sugar: White wheat bread has an average GI of ~75 (glucose scale) pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Table sugar (sucrose) has a GI around 65. That means gram-for-gram, white bread can actually raise blood sugar faster than plain sugar! Of course, we usually eat more bread (one or two slices = ~30g carbs) than we would eat straight sugar at once, making the glycemic load of a bread-heavy snack quite high.

Takeaway: Don’t assume a starchy food like bread is automatically gentler on blood sugar than sugary candy – the numbers say otherwise.Whole Wheat Bread: With a GI of ~74 pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, whole wheat or wholemeal bread is almost identical to white bread in glycemic effect. Its extra fiber and nutrients make it a better overall choice nutritionally, but portion control is just as crucial. Two large whole wheat bread slices (~34g carbs total) will have a glycemic loadin the 20s (high GL), similar to two slices of white.

Takeaway: Whole grain bread is “better” mostly because of fiber, but it won’t save you from a sugar spike if you overeat it. Treat bread as a carbohydrate to enjoy in moderation, not an unlimited “free food” just because it’s whole grain.Candy Bar (Chocolate with Nuts): A standard chocolate bar with nuts (like a Snickers) has a moderate GI, roughly 40–55 (exact value varies by recipe). The fat and protein slow down the absorption of its ~30g of carbs. So the glycemic load of one candy bar might be around 20–25 (moderate to high).

Takeaway: Candy bars do cause blood sugar to rise (and they pack a lot of sugar), but the spike might be a tad slower than an equal carb amount from white bread. Don’t be fooled though – candy delivers loads of empty calories. The lower GI is not a license to indulge; rather, it’s a reminder that adding protein/fat (like nuts) to carbs can blunt spikes a bit.Granola Bar: Many granola or cereal bars masquerade as health food. In reality, they often contain 10–15g of sugars (sometimes labeled “brown rice syrup,” “honey,” etc.) plus quick-digesting refined grains. One study even classified a supposedly “healthy” dried cranberry cereal bar as a high-GI food (GI ≥ 70) pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Even when marketed as “sugar-free” with sugar alcohols, cereal bars can have high available carb content that raises blood glucose quickly.

Takeaway: Granola bars can be as glycemic as a candy bar, especially if they are low in fiber or protein. Always check the carb and sugar content – a 150-calorie bar that packs 25g of carbs (with little fiber) will hit your bloodstream nearly as fast as a cookie.Candy (Pure Sugar Candy): For comparison, a pure sugar candy like jellybeans or gummy bears (virtually 100% sugar, no fat or protein) will have a very high GI (possibly 80–90) and a high glycemic load if you eat a standard serving (which might be 30–40g of sugar). This is the worst-case scenario for blood sugar – lots of simple carbs, nothing to slow it down.

Takeaway: These are clearly “bad carbs” in the conventional sense and indeed cause rapid spikes. If you’re indulging, keep portions very small – a little goes a long way (unfortunately in the wrong direction for your glucose levels).Fruit vs Fruit Juice: A medium orange (about 15g total carbs, GI ~43) pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov has a low glycemic load and a gentle effect on blood sugar for most people. A glass of orange juice, however, might contain 30g of sugar with little fiber, leading to a quicker, higher spike.

Takeaway: Whole fruits often qualify as “good carbs” because their fiber and water content moderate the sugar hit, whereas juices act more like a soda. Always prefer eating the whole fruit over drinking fruit juice, especially if blood sugar stability is a concern.

These comparisons drive home a crucial point: the context and quantity of the carbohydrate matter as much as the type of food. A whole grain bagel and a doughnut might affect your glucose more similarly than you’d think (the bagel has more fiber but also more total carbs!). A small piece of chocolate after dinner might have less impact than an extra serving of “heart-healthy” brown rice at dinner. This isn’t to suggest chocolate bars are healthy – rather, it’s to bust the myth that you can ignore portion just because a food is dubbed a “good carb.” All carbs turn into glucose; some just do it faster or slower, and some come in larger packages than others.

Final Thoughts: Take Charge of Your Carbs

It’s time to throw out the simplistic rulebook of “good carbs” vs “bad carbs.” The truth is more nuanced – and more empowering. You don’t have to demonize all bread or swear off the occasional treat; instead, focus on understanding your carbs and owning your portions. Glycemic index and load are handy tools that reveal which foods are more likely to send your blood sugar on a rollercoaster. Use that knowledge: favor carbs that are high in fiber and nutrients (vegetables, legumes, intact whole grains, whole fruits) since they tend to have gentler effects. But equally important, mind how much you eat. A modest serving of even a high-GI food might be just fine, especially if paired with protein or healthy fats to slow absorption. Conversely, overeating even “healthy” carbs can leave you feeling sluggish and hungry an hour later when your insulin kicks in and blood sugar plummets.

Be wary of food industry hype. If a cookie box proclaims “made with whole grain” or a cereal bar says “no high fructose corn syrup,” remember that these could be distractions from the real issue – maybe that cookie still has 20g of sugar, or that cereal bar is essentially held together by honey (sugar is sugar). Arm yourself with facts: check labels for total carbohydrates and added sugars. Recognize the code words for sugar (there are many!). And notice the serving sizes too – companies often make them unrealistically small to hide sugar per serving. Don’t let the health halo of “good carbs” trick you into overeating them.

Most of all, listen to your body. Some people genuinely feel better (more energetic, no sugar crash) when they stick to low-GI, lower-carb eating. Others can handle carbs well, especially around exercise. Pay attention to how that big bowl of pasta makes you feel versus a smaller portion with some grilled chicken added. Pay attention to whether that 10am granola bar really satisfied you or if you got the munchies soon after. Your energy levels and hunger signals can often tell you if a carb choice was a bit too much for your system.

In the end, the goal isn’t to label carbs as strictly good or bad, but to make informed choices. Carbohydrates are not evil – they’re a vital source of fuel and pleasure in our diets. The key is managing them wisely: choose quality carbs most of the time, but also choose quantity wisely all the time. By busting the myths and understanding concepts like GI and GL, you can enjoy carbs in a way that supports steady blood sugar and better health. The power lies in your hands and your portion sizes – not in the marketing labels on the box. So the next time you plan a meal or reach for a snack, think beyond “good vs bad” and consider the whole picture of that food. Your blood sugar (and overall wellness) will thank you.

Empower yourself to rethink your relationship with carbs. By seeing through the food industry’s myths and focusing on science-backed facts, you can take control of your diet and health – one informed carb choice at a time.

Scientific References on Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL)

Atkinson FS, et al. (2021).

International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values 2021: a systematic review.

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 114(5), 1625–1632.

🔗 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34258626/Jenkins DJA, et al. (2021).

Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cardiovascular disease and mortality.

The New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1312–1322.

🔗 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2007123Barclay AW, et al. (2008).

Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies.

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(3), 627–637.

🔗 https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/87/3/627/4633321Livesey G, et al. (2013).

Is there a dose-response relation of dietary glycemic load to risk of type 2 diabetes? Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 97(3), 584–596.

🔗 https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/97/3/584/4577081Liu S, et al. (2000).

A prospective study of dietary glycemic load, carbohydrate intake, and risk of coronary heart disease in US women.

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 71(6), 1455–1461.

🔗 https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/71/6/1455/4729324

Coca-Cola’s Influence on Nutrition Messaging and Public Health

Serôdio PM, et al. (2020).

Evaluating Coca-Cola's attempts to influence public health ‘in their best interest’: analysis of internal documents.

Public Health Nutrition, 23(14), 2520–2530.

🔗 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/evaluating-cocacolas-attempts-to-influence-public-health-in-their-best-interest-analysis-of-internal-documents/AF1F55B4C505E7996C28CBB1A1628C90AP / Candice Choi (2015).

Coca-Cola Funds Scientists Who Shift Blame for Obesity Away From Bad Diets.

Associated Press (via New York Times).

🔗 https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/10/health/coca-cola-funds-scientists-who-shift-blame-for-obesity-away-from-bad-diets.htmlGillan Oakenfull (2023).

The Bitter Aftertaste of Coca-Cola’s ‘Neutral’ Marketing Strategy.

Forbes.

🔗 https://www.forbes.com/sites/gillianoakenfull/2023/09/12/the-bitter-aftertaste-of-coca-colas-neutral-marketing-strategy/Time Staff (2016).

Soda Companies Fund 96 Health Groups in the U.S.

Time Magazine.

🔗 https://time.com/4522940/soda-pepsi-coke-health-obesity/Reuters Staff (2024).

Lawsuit Accuses Major Food Companies of Marketing ‘Addictive’ Food to Kids.

Reuters.

🔗 https://www.reuters.com/legal/lawsuit-accuses-major-food-companies-marketing-addictive-food-kids-2024-12-10/